Ursa Health Blog

Visit Ursa Health's blog to gain healthcare data analytics insights or to get to know us a little better. Read more ...

The imperative to collaborate to achieve common goals has long defined human interactions. Initially, this imperative was rooted in survival, but working in partnership is no less important today than it was for our ancestors.

Although we have long practiced collaborative problem solving in the business world, it’s not uncommon for projects, which are essentially collaborative endeavors, to meet roadblocks caused by individuals with wants and needs antithetical to the aim of the project.

I have spent most of my career working in analytics. From data warehouse development to managing advanced analytic projects, I have seen the amazing results that come from effective teamwork and the nightmarish scenarios that arise when stakeholders become intractable and uncooperative.

I once participated in a consulting engagement with a an incredibly friendly individual, who I’ll call Jacob, who absolutely refused to cooperate with the consulting team. Jacob had developed an intricate data extraction and transformation process imbued with a significant amount of business logic and was unwilling to share it with our team. However, our ability to understand and refine this process was central to the success of the engagement.

Our client did not have direct authority over Jacob and had a strained relationship with his manager. Meetings were scheduled, and Jacob would not attend. He was asked to share his code and would only provide single scripts.

This situation is familiar to many of you, I am sure.

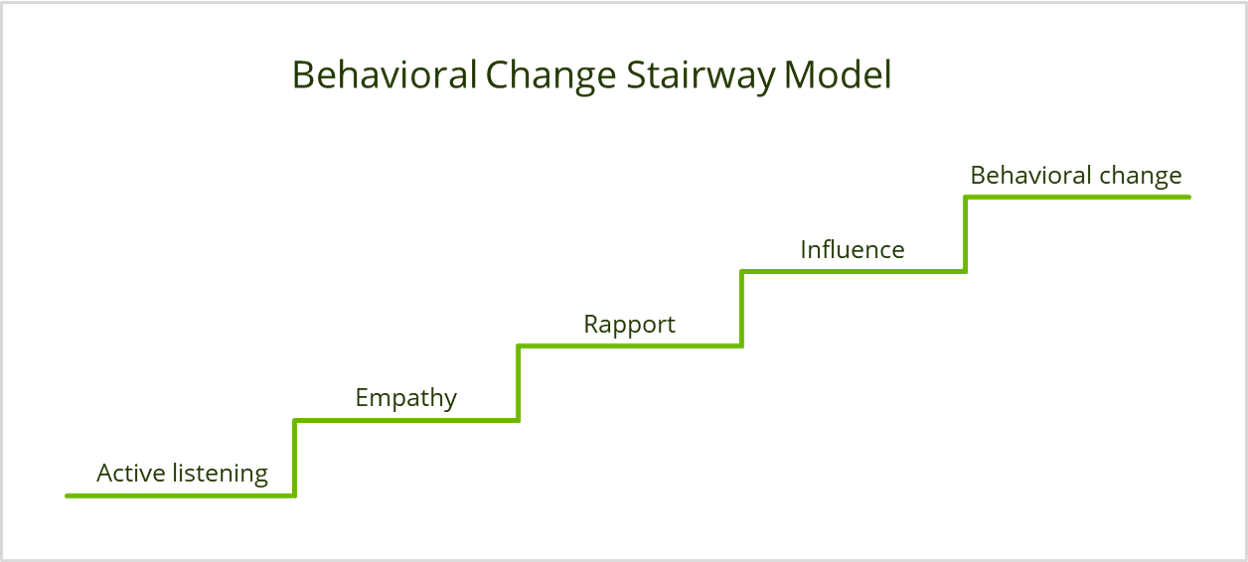

So, how was the situation resolved? I decided to treat Jacob as a hostage taker and utilized the FBI’s Behavioral Change Stairway Model (BCSM) to negotiate. The model, depicted below, has five steps.

Active listening

This step encourages conversation using open-ended questions and paraphrasing one’s understanding of his or her counterpart’s story. It attempts to subtly identify and confirm emotions that the other side has expressed and utilizes intentional pauses in the conversation for emphatic effect.

With this in mind, I invited Jacob to lunch at an expensive restaurant hoping that would encourage him to spend an hour with me. It did. We met, and after some small talk, I gently asked him about his reluctance to work with us and then actively listened. He explained that he had been with the company for ten years, and he was afraid that if our firm automated the work he was doing, he would be out of a job.

Now we were getting somewhere.

Empathy

The intent of the second step of the BCSM is to convey empathy with your counterpart. It is a genuine demonstration of one’s interest in and understanding of the perceptions and feelings of the other side.

This was easy. In fact, it would have been difficult not to empathize with Jacob’s perceived dilemma. Through the conversation, I was able to demonstrate to him that I was interested in his problem and wanted to help.

Rapport

The end product of active listening and empathy is increased trust. This trust is furthered through conversation that positively reframes the situation and explores areas of common ground.

It is amazing how illuminating a little information can be. I now understood his problem, had shown that I cared about it, and was ready to pivot the conversation toward our shared interests. As we continued to talk, Jacob shared that he did not want to obstruct our project but was afraid of what would happen if he did not. This was it: the common ground we needed to work from.

Influence

Once rapport has been established, one can begin to make suggestions and explore potential solutions while being mindful of the alternatives available to their counterpart.

Once Jacob signaled he was willing to work with us, I was able to explore options that might be appealing to him. I invited him to propose ideas he thought were appealing, and we discussed the merits of each.

Behavioral change

Achieving the last step in the BCSM is contingent upon how well the first four steps were executed. Proposed solutions are chosen that lead to the desired behavioral change.

After exploring several options, we settled on pulling Jacob closely into the project so that he would be intimately familiar with the data warehouse we were building. This put him in a position to be an expert on the new system, which ensured he would have the security he desired.

So, lunch went well, but the important question is what happened afterward. After all, negotiated agreements are only as good as their implementation.

Later that afternoon, my team received the full code set and table extracts from Jacob. We had everything we needed to carry on with our work. Our team was happy, the client was happy, and, most importantly, we made an ally who became an expert on the new data warehouse.

Useful tools

The BCSM provides a framework for dealing with tough situations in which individuals are reluctant to cooperate. It also provides a useful set of tools for building and strengthening relationships with stakeholders who are collaborative from the start. While I wish that all your analytic projects are smooth and seamless, I encourage you to use the BCSM to deal with the ones that are not.